Call it balance, integration, or sway. No matter the name, the goal is the same: to combine work and life in a way that feels purposeful and possible. That aspiration seems increasingly urgent in the wake of a pandemic that's prompted many of us to reprioritize health and our family.

A glance at recent headlines suggests it might be more achievable going forward. Buffer and Kickstarter are implementing four-day workweeks. More and more organizations are offering backup childcare and mental health benefits. Almost half of companies have made or plan to make changes to their vacation, sick leave, or PTO programs to boost flexibility, according to a Willis Towers Watson survey. Citigroup, Ford, and Target are just a few of the Blue Chips that have announced that some employees can work from home part-time.

It all adds up to an emerging consensus from corporate America: Give employees more time and resources to take care of themselves and their family.

But researchers who specialize in gender in the workplace warn that while balance might be more attainable now for a few lucky folks, the long-term forecast for a more reasonable approach to work is still unclear.

"It's a mixed picture," says Joan C. Williams, a distinguished professor of law at the University of California, Hastings School Law, and the founding director of the Center for WorkLife Law.

We're Working More

When COVID-19 forced many offices to shutter for weeks or even months, some people predicted that professionals would spend their newfound free time — freed from a long commute and untethered to a desk — baking focaccia and marathon training. That's not what happened.

In the wake of daycare and school closures, parents devoted long hours to childcare and teaching. More than three million women dropped out of the workforce entirely. Employees who held onto their jobs worked longer hours than they had before.

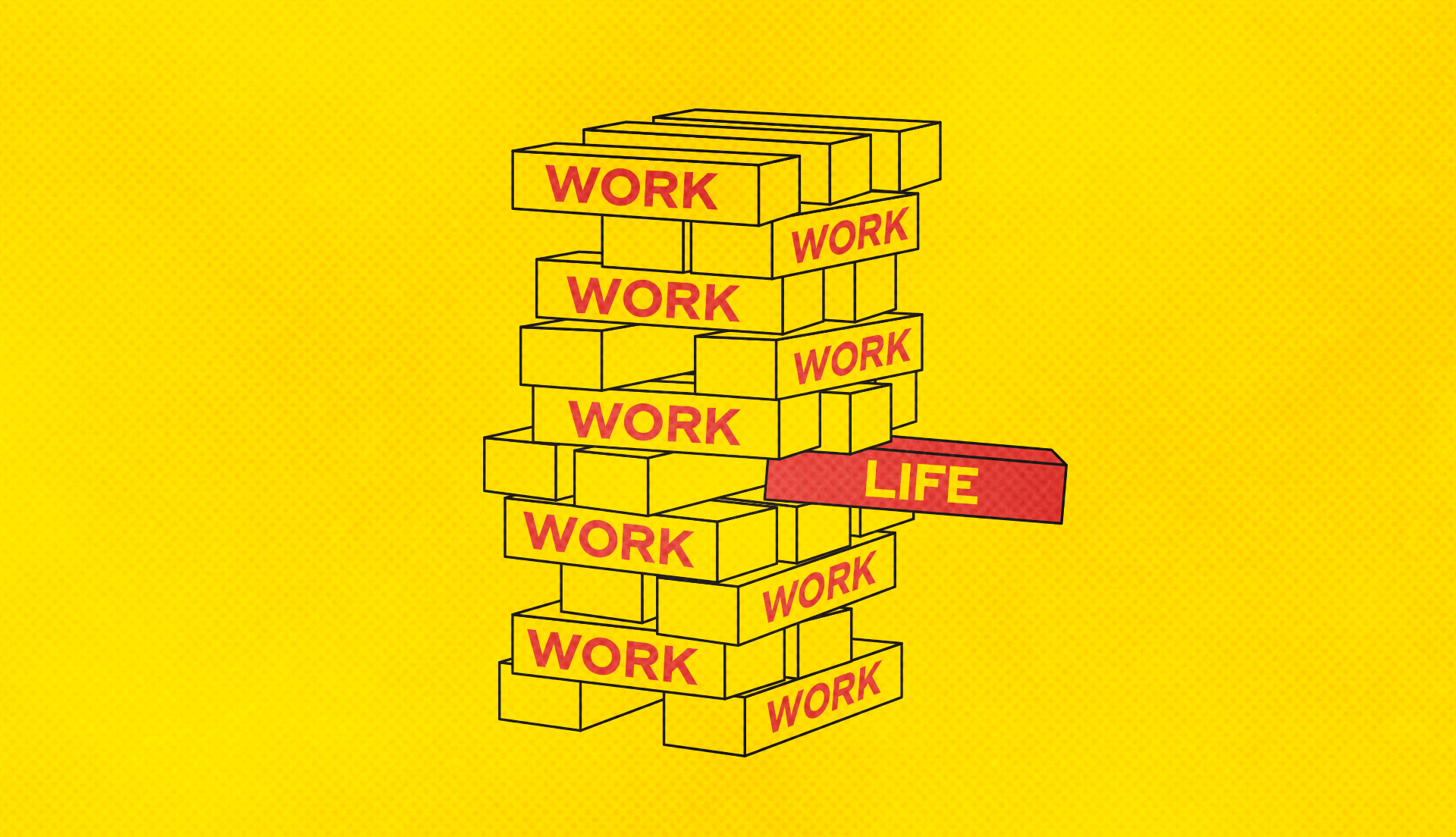

In fact, a working paper at Pepperdine Graziadio Business School found that ideal worker norms — the expectation that employees prioritize work over all other parts of their lives — became more entrenched during the pandemic. The authors interviewed 53 working moms, and found that ideal worker culture was reinforced within their organizations in three ways: "through intensification of work, reinforcement of the masculine aspects of work culture, and the temporary nature of support in absence of a clear and actionable support policy." In other words, the moms worked longer hours, felt pressure to perform (or else), and only received brief reprieves.

"There can be a company or even a unit within a company that really espouses itself as family-friendly, but there can be stopgaps at the management level," says Dana Sumpter, a co-author of the paper and an associate professor of organization theory and management at Graziadio. "Plenty of respondents said, ‘My company has these great policies, but I don't take advantage of them, because I know my manager would not be supportive.'"

There's a good chance those moms are right. Previous research has shown that employees who take advantage of benefits like flexible schedules and maternity leave are deemed less competent and committed. This "flexibility stigma" is one reason why women, who are more likely to serve as the primary caretaker for a child or aging parent, have less representation in the executive ranks than men.

"I'm not seeing evidence that workers, or at least women workers, are being less penalized now for wanting things like paid time off, flexible schedules, or more reasonable work hours," confirms Jessica Calarco, an associate professor of sociology at Indiana University.

Why Long Hours Persist

Even without penalties for scaling back, most ambitious professionals understand it pays to put in the hours — literally. Employees who work 50 hours or more earn up to 8 percent more an hour than similar people working 35 to 49 hours, according to a 2019 sociology paper. The wage premium for working long hours is especially true for managerial jobs and in professions like finance, law and consulting.

It's too early to know if the pandemic put a dent in America's penchant for long hours, but there are plenty of reasons to be skeptical. Namely, many leaders see it as essential for success, especially for early-career professionals. Scott Galloway, a bestselling author and marketing professor at New York University, has argued that "balance is a myth." Elon Musk once tweeted that "nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week." Recently, Jordan Kong, a California-based venture capitalist, said in a now-viral Twitter thread that "the best thing young people can do early in their careers is to work on the weekends."

The Case for Optimism

Even so, experts say there are a few reasons why we might emerge from the COVID-19 era with a bit more balance. First, the rise of remote work provides a "huge step towards workplace flexibility for many, many people," Williams says. With so many well-known companies committing to hybrid or remote workplaces, and a tight labor market putting pressure on their competitors, employees will continue to have more opportunities than ever to find flexible work.

"Workers, especially younger workers, really do care about doing less commuting and having more control over their lives," Williams says. "They always have, but there haven't been enough businesses that offer it to make it a point of competition. Now there are."

Another silver lining of our newly remote world, Sumpter says, is that managers gained visibility into their employees' daily lives — and challenges.

"The hope is that it has engendered empathy — the ability to walk in a working mom's shoes," she says. "If there's more awareness and understanding of that lived reality, that could help to fuel choices to allow and support flexible work practices."