The pandemic changed not only where we worked but what we wore to work when “work” was one foot away from bed. Pajama-style satin shirts quickly became en vogue over pantsuits. And bras? Forget about it. But now as hybrid offices are becoming the norm and in-person happy hours have returned, the question needs to be asked: What does a ‘professional’ look like?

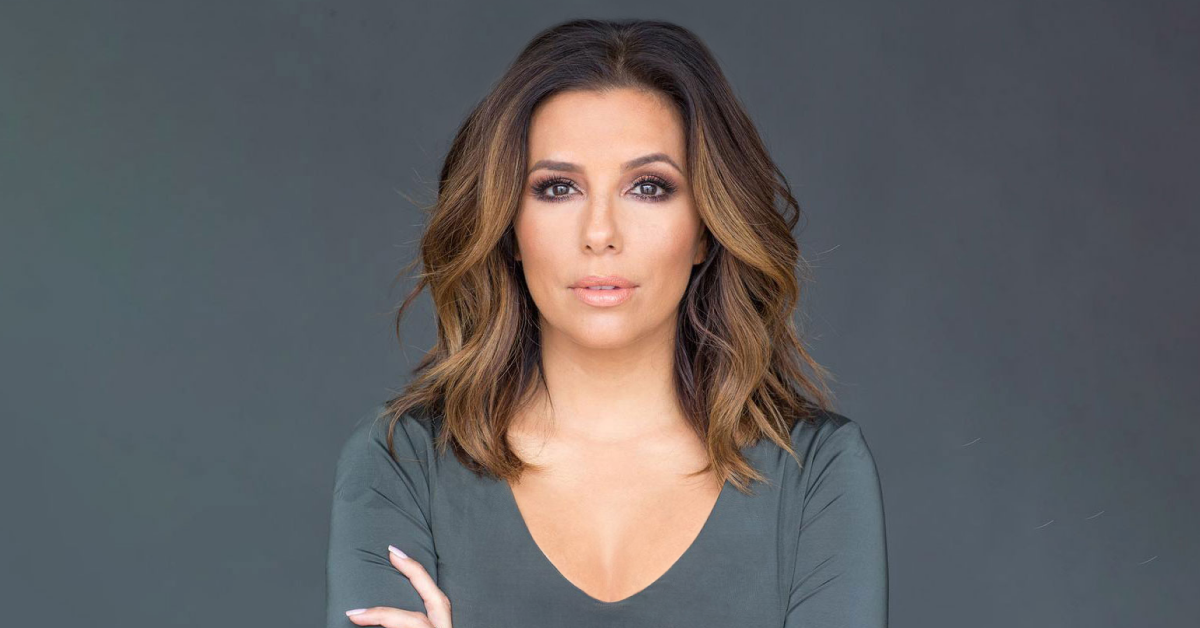

“The archetype that many leaders hold around what a professional should look like is, frankly, biased,” says Ritu Bhasin, Chief Executive Officer and Founder of bhasin consulting inc, and author of The Authenticity Principle. “Most organizations in the U.S. are led by men and white men in particular, so there is a real bias in favor of looking like that prototype.”

In fact, the whole idea of professional dress is shaped and upheld by that norm. “The premise of professional dress is typically to look neat, presentable, and trustworthy,” says Rachana Adyanthaya, image consultant, executive coach, and Founder at Cr8MyChange. “But along the way, the visual images of ‘neat’ and ‘presentable’ have intertwined with a cultural identity that doesn't lend itself to all members of society.”

Surveys show that more than 80% of employees say they performed better when they’re dressed comfortably and more like themselves. The feeling of being stuffed back into a professional dress box can be especially acute for women and women of color. Black women in particular were reluctant to go back to the microaggressions they commonly experienced in the office, with a 2021 Slack survey showing only 3% of Black knowledge workers wanted to return to the office full time.

“We don’t want to depress our authenticity any longer,” Bhasin says. “I want to do my hair the way I want to do my hair. I want to wear what I want to wear. I don’t want the pressure to have to put makeup on or wear a dress.”

Unsurprisingly, the group most excited to return to the office post-pandemic, by far, was white men. One survey from March found that 30% of white men wanted to return to the office, compared to 22% of Black and white women, and just 16% of Black men.

Professional dress expectations have done undue harm to non-white people in the workplace. Black women have fought numerous court cases against employers who refused to allow natural hair and hairstyles, with mixed results. Today, there’s still little widespread legal protection against discrimination based on hairstyles.

Even when there is legal protection based on religious dress (such in the case of Sikh men who wear their hair wrapped in a turban or Muslim women who wear hijabs), unspoken cultural norms on what employers think customers “prefer” still invite discrimination. “While the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) says that customer preference is not a sufficient reason to deny an employee’s request to wear religious attire, this does not prevent this bias taking place in the workforce. It just won’t be verbalized,” says Adyanthaya. Non-white employees know this and feel pressure to conform and code-switch in order to be accepted in their industries.

Even when leaders themselves may not care what their employees wear, they can require a certain standard of dress when under pressure to present a certain image with clients. “They say ‘If our employees don’t dress in that traditional white male-centric way of dressing, then clients are going to think we’re not smart enough, or professional enough, and then we’re going to lose money’,” says Bhasin. “It prioritizes profit over inclusion.”

Instead executives may choose to openly address the issue. Bhasin suggests, “You can tell them that, given the shift in workplace culture, you're no longer going to adhere to that standard, but you’re still going to provide excellent service.”

The key to supporting any dress code, be it casual or formal, is to be explicit on what ‘professional’ attire and ‘casual’ attire means. Companies should survey their employees directly to find out what they want and find a consensus with what the business needs. Once a dress code has been reached, it’s important to be really clear on the expectations. For example, flip flops may be okay in the office, but not when meeting with the board. If there are unspoken assumptions, it’s better to say them out loud so that there isn’t room for misinterpretation.

Leaders also should model a more authentic dress style if they are genuine in wanting their teams to do the same. “If team members are saying, I want to dress casually at work, but you continue to dress in formal business attire, your actions are not in alignment with what you’re saying,” says Bhasin.

This doesn’t mean you have to start showing up in the office with your 15-year-old holey band t-shirt, but it can start small, like going without makeup if you don’t like wearing makeup. This can start the shift into showing up more authentically. For Bhasin, this meant getting her nose pierced, a common Indian practice, but still one she felt self-conscious about when presenting. And while she started with a small stud, she found she liked wearing hoops more, but went back to the smaller piece when she was presenting until one day she decided to leave the hoop in.

“I was presenting for the global chairs for a consulting firm, and decided I didn’t want to take it out; I wanted to share it,” she says. “Of course it was a non-issue, and now many years later, I have a jewel-encrusted nose ring I wear everywhere and anywhere. If I could meet the President of the United States, it would be with my blinged out nose ring.”

When leaders show up in this kind of full authenticity, they are not only more connected to themselves and happier personally, but are giving agency to their team members to do the same.